Background

Automation test frameworks should run tests in the simplest way possible. However, we often over-engineer them by attempting to make one grand solution to support automation of a wide variety of tests. This results in layers of indirection, unnecessary technical debt, and typically— inefficiency. “Peeling the onion”, so to speak, thus becomes an imperative exercise to ensure a test framework’s evolution in the right direction.

As with many large open-source efforts, some automation and tooling come via contributions from participating members of the community. This is the case with some of the automation scripts in the AQAvit project. The System Test Framework (STF) and aqa-systemtest which was originally contributed by IBM contain some of the automation that was also initially used for triggering the runs of the licensed Java Technology Compatibility Tests (TCKs) as part of the Temurin Compliance project.

It is important to note the difference between automation used to trigger ‘any’ test material versus the TCK test material itself and the rules that govern that it be kept private. The TCKs are run in private by distributors with a license to that material. At Adoptium, this activity is done in the Temurin Compliance project.

The Big onion

This is a story of reducing complexity. Given the provenance of some of the automation scripts, let’s look at a real-world example of the simplification of test pipelines. A large set of Java Technology Compatibility Tests (TCKs) is run as part of Java compatibility verification process of all compliant JDK distributions, including Eclipse Temurin binaries, Semeru OpenJ9 certified edition, IBM JDKs and any distribution being listed in the Adoptium marketplace. Historically for IBM JDKs, these TCKs used to be driven via an age-old cryptic Perl wrapper which was difficult to maintain and evolve to fit the needs of newer JDK versions.

At one point we decided to replace this legacy TCK Perl wrapper with a new test framework that was being designed to drive stress tests — the System Test Framework (STF). This was also the point at which these frameworks were open-sourced. However, we soon decided that STF was simply too lofty for the needs of TCK execution. First, STF would need users to define test cases as a series of conceptual ‘stages’ written in Java code. It would then take those ‘stages’ and generate a set of Perl scripts to orchestrate the second layer of Java command lines which would culminate in the eventual automated test job in the Continuous Integration (CI) system. While this has benefits in terms of debug-ability of load/stress tests, it was not the best way to drive the TCK, which itself comes with its own sophisticated test harness, the Java Test harness which is publicly documented in Oracle’s Help Center under the Testing Tools section if you wish to learn more.

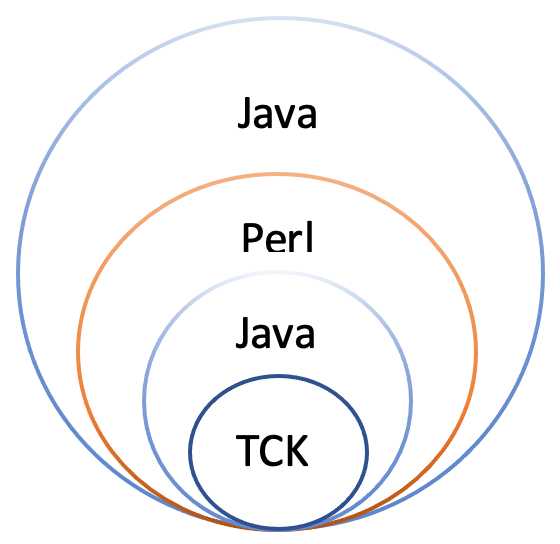

Result—the ‘Big Onion’. By adopting STF to run TCKs, not only did we introduce unnecessary layers of indirection in our automation story (Java -> Perl -> Java), but we also ended up incurring additional compilation time in TCK builds in our CI system, since STF requires checking out and compiling from both its own Git repository, as well as one extra Git repository that of the System tests.

Peel the onion

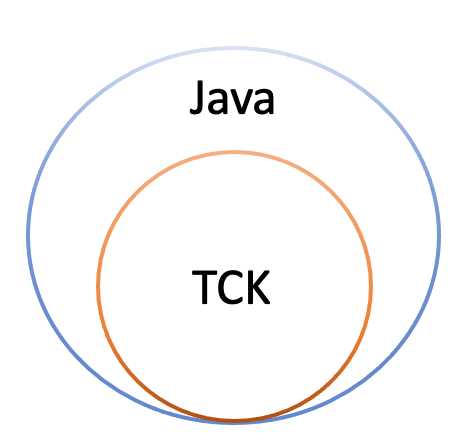

So, to run the TCK harness with less indirection and more efficiency, we decided to decouple it from the STF stress test framework altogether and replace it with JavaTestRunner– a simple Java class that can perform the essential tasks of generating command files for TCK, building a result summary, starting required services and managing execution of the TCK harness itself.

Unlike the STF framework, JavaTestRunner is housed within the same Adoptium aqa-tests repository as the rest of the AQAvit test suites. This relieved us from having to checkout and compile two additional repositories— resulting in a dramatic reduction of compile time for TCK CI jobs (we ended up saving ~3,285 hours of machine time per year).

Peel it more

Stripping out layers of indirection from test frameworks typically happens in iterations. JavaTestRunner gave us the ability to run TCK jobs faster, with more debug-ability and less indirection. However, it still was an ‘onion’. Meaning a few more layers could potentially be peeled off still.

One such layer was how JavaTestRunner drives the TCK harness itself. The TCK harness is a Java application itself. JavaTestRunner would gather all the inputs from user via a playlist, construct the command-line and run the TCK harness via ProcessBuilder. This layer of indirection (JVM->JVM) is not only inefficient, but it also results in hiding test command-lines— making the TCK builds harder to debug.

The above issue was solved by stripping out JavaTestRunner and replacing it with JavaTestUtil. JavaTestUtil performs the essential tasks of command file generation and result summary generation only, while the actual command-lines to start required services and running the TCK harness are placed in a makefile outside of the Java wrapper. This means one less layer of indirection and faster execution. Plus, users now have more visibility to the actual command-lines that are executed for each TCK test target.

Summary

Ultimately this continual refinement and simplification of the process is what we all work to achieve. It is stated as part of the ”continual investment” section of the AQAvit manifesto. Stating it in the guidance criteria by which we run our projects means we judge our progress by how effectively we reduce technical debt and complexity.

Test frameworks tend to evolve into ‘Big Onions’. Peeling those onions should be considered among software development best practices. It helps us and the development teams who use our automation scripts to reduce technical debt while continuously improving quality assurance automation efficiency.

Do you have questions or want to discuss this post? Hit us up on the Adoptium Slack workspace!